Where Is the Gate? Woodstock Operations

The Woodstock Museum in the Bethel Woods Center for the Performing Arts gives an excellent overview of the world’s most famous music festival. “Woodstock” stands apart as more than a music festival. It is a major part of American history and the 1960s, and the focus of an untold number of studies. A recent trip to the museum sparked my curiosity to learn more.

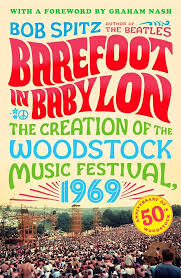

Journalist Bob Spitz’s Barefoot in Babylon: The Creation of the Woodstock Music Festival, 1969, is perhaps the best account of how the event came together. Reprinted many times, the book relies heavily on first-person accounts and solid research into the cast of characters and the multiple machinations that made the festival special. Spitz has penned biographies, books, and articles for decades. Especially relevant to the history of Woodstock, he worked in popular music, managing Bruce Springsteen and Elton John. Spitz writes from an informed perspective and his interest is very much in logistics. How did the damn thing come together?

As a refresher, Woodstock was a three-day music festival held in Bethel, New York, in August of 1969. Nearly half a million attended and heard many of the most vital musicians of the time. While it was originally supposed to be a profit making concert with 50,000 attendees, massive logistical problems led to a venue change and free admission, for they couldn’t control the crowd or take tickets. The problems cannot be understated – they were enormous. Nonetheless, the event was remarkably peaceful, even with three deaths and untold numbers of issues, from water to electricity to traffic. In sum, it was a beautiful mess, like a party when 10x as many guests arrive. On a totally different scale, with a documentary and a firm place in popular culture and history.

Spitz’s book is enormously interesting, especially to those curious about event promotion, planning and execution. He goes into great deal regarding the financing, the coordination (or lack thereof), and the thousands of small decisions that shape an event. The lighting and sound system posed challenges, for example, and who, why and how the problems were addressed makes for an engaging tale. The people involved in security make up another important thread. Fear of hippies and the counterculture ran deep. Figuring out how to keep people safe and de-escalate problems was no small task.

The medical situation takes up a big part of the book. It makes sense, too. There were few rules or guidelines for this kind of event at that point in time. The haphazard nature of the festival, as it emerged over the months, called for real leadership and innovation. Kind of in the weeds, to be sure, but it adds up. The deep local resistance to the “hippies” added an extra level of stress.

What Spitz does not examine in much detail are the larger questions about why so many attended, why so many have been drawn to the festival over the decades. To be sure, the list of artists who performed is extraordinary. We don’t think of Woodstock, though, as a 1969 greatest hits festival. Other factors were afoot, other trends and moments. Many others have looked at those questions, and I look forward to following up and learning more.

For how to – and not to – put on a festival, though, I heartily recommend Barefoot in Babylon. And a massive thumbs up, too, for the extraordinary Max Yasgur, the conservative Republican Jewish dairy farmer who stepped up to give the festival a home after the original site fell through. He was truly a special human being.

David Potash