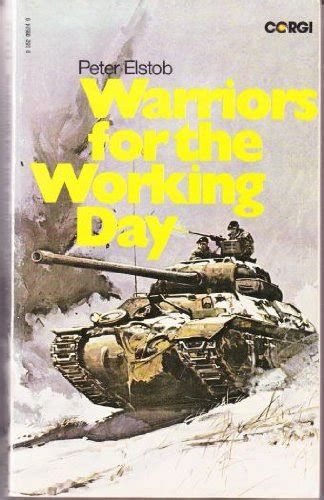

Warriors For The Working Day – Classic WWII

In Shakespeare’s play Henry V, King Henry tells a Frenchman before the Battle of Agincourt that “we are but warriors for the working day; our gayness and our gilt are all besmirch’d with rainy marching in the painful field.” Not a boast, it is a statement of fact regarding the commitment and sand of the English soldier. “But, by the mass, our hearts are in the trim” the soliloquy ends. Powerful and moving.

Peter Elstob lifted the quote for the title of his outstanding WWII novel about tank warfare. It’s an apt choice. Warriors for the Working Day is a superb book about the day-to-day of fighting in World War II from the solder’s perspective. It is beautifully written and extremely compelling, pulling the reader into the grit and internal stresses of the war. Most importantly, it is lightly fictionalized. Elstob knew the subject, personally and intimately, and that knowledge informs the entire endeavor. Published in the 1950s, it has resonance and impact today.

Gripping and engaging, the book is sprinkled with literary allusions and devices. The novel is structured into two parts. Book One, “First Light” is based on when it’s possible to distinguish between black and white. Book Two, “Last Light” is when it’s no longer possible to distinguish. The structure is literal and metaphorical, capturing the kinds of battles the soldiers’ face and the arc of the war through a soldier’s eyes. There is action, drama, and quite a bit of thoughtful reflection. Elstob’s skill allows one to enjoy the book’s prose, too. His writing is that good.

One character, Brooks, functions as the key thread throughout the novel, anchoring the action and the plot. However, the novel explores more than Brooks and his growth as a tank commander. We meet the senior officers and soldiers who school him, his colleagues, the men he commands, and a wide range of people he encounters in England and Europe. The book opens with training before D-Day and ends as the tank command is in Germany, heading toward the war’s conclusion. Characters come, go, live, die, and through it all, the soldiers must fight. They also have to fight in order to fight. The stresses, the demons, the pressures are constant and debilitating.

Warriors for the Working Day stands as a powerful corrective to narrative war history, the kinds of books that explain battles with maps, arrows and charts. With outcomes known, they give sense to what is inherently impossible to comprehend. Those kinds of history books are necessary but far removed from the actions of the poor folks who have to drive the tanks, shoot the weapons and hope for the best. There’s an immediacy to Elstob’s writing that carries you directly to the battlefield, to the bureaucracy, and the day to day. He is particularly good in his characterization. Everyone seems more than real.

Elstob’s personal war experiences made certain of the reality. He was a Royal Tank Regiment volunteer (his attempts at the RAF were unsuccessful). Elstob saw action in Asia, Africa, England and Europe. He lived through all that is recounted in Warriors for the Working Day. Moreover, he penned several military histories. Elstob truly knows his subject and that shines through his writing.

Massive thanks to the Imperial War Museum for reissuing this classic novel. It was as strong as anything new that I’ve read in years.

David Potash