Dispatches of Chicago Violence

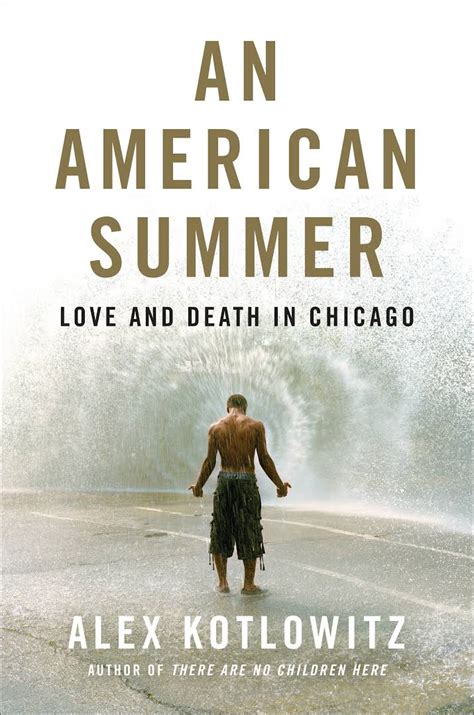

An American Summer: Love and Death in Chicago is a heart-wrenching account of the horrific impact of gun violence on the south and west side of the city. Written by Alex Kotlowitz, a Chicago-based journalist and writer whose work consistently focuses on issues of justice, the book captures the voices of those directly affected by the seemingly endless cycle of shootings and shootings. It is an extraordinarily sad tale.

The geography of the book is constrained to the primarily Black and Hispanic neighborhoods of the city, just as the high-levels of violence in Chicago are similarly bounded. There is no substantive framing, no trends, and no meaningful bigger picture context. Kotlowitz is not interested in charts, tables, studies by criminologists or governmental reports. The pieces in this work are “dispatches” from an all too common summer, he tells us. It is only in the book’s latter part do we hear more from the voices of politicians and the police.

Kotlowitz dives into the lives of individuals, the men, women and children directly affected by the violence. He talks with former gang members, with young men awaiting trial, with the mothers and fathers of those killed and injured. Kotlowitz is a very good listener and his stories and profiles are richly drawn and suitably complex. He is interested in these people as people. That, in and of itself, is powerful. American Summer is an important corrective to what is often reflected in media and popular culture.

Researching the book took Kotlowitz four years. He talked with about two hundred people. The structure of the book appears to be chronological, but he weaving together a series of snapshots, individual stories of hope, violence and struggle. The recurring theme is one of PTSD. Each and everyone of the people involved in the violence is wrestling with the consequences of violence. It is pervasive and crippling.

One man is struggling, after prison and decades of guilt, with the consequences of shooting another teenager. Another struggles with drug addiction years after many in his family died in a fire, an arson caused by neighborhood street violence. A smart high school student joins other gang members and is rightfully arrested. Relatives and neighbors refuse to give testimony about a young man who committed a murder. It as another expression of a culture of fear and an ingrained sense that little or nothing can be done. “It is everywhere,” Kotlowitz writes. The sorrow of the parents and the grandparents is overwhelming.

For example, Kotlowitz breaks the wall of reporting and writes to us directly about the violence surrounding one individual, Thomas. A friend’s cousin is shot twice on his block. A friend shot and murdered at a corner liquor store. Another friend from high school killed by a gun, perhaps accidentally. A different friend shot six times and blinded. The older brother of another friend shot and killed. Yet another friend shot and killed, this time by a fourteen year old. What kind of life is possible in that kind of environment?

The strength of An American Summer is Kotlowitz’s focus on the personal. The book is humanizing, even as the stories are horrific and overwhelming. However, it is impossible to read and not want attention, investment, engagement and action to help these people. On that front we have to look elsewhere, beyond this narrative. An American Summer makes a compelling case for great interest and understanding by all of us in the violent neighborhoods of Chicago.

David Potash