Which Side Is The Other Side?

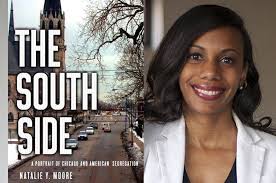

Natalie Y. Moore is a product of the South Side of Chicago. For those who do not know Chicago, “North Side” and “South Side” conjure up much more than a region. They embody a history, a mindset, and a way of life, separate and distinct from each other. They are often about race and ethnicity. Many who live in the city think of their home as a neighborhood, not the larger city. In all there are 77 of neighborhoods and together they make Chicago a fascinating and dynamic metropolis. Yet the sides of the city are not easily thought of as one, as expertly chronicled by Moore in her book, The South Side: A Portrait of Chicago and American Segregation. Racism and geography can create destiny.

Moore is a journalist. She reports on the South Side for WBEZ, Chicago’s NPR station. She has covered other cities and other countries. Her writing is in newspapers and national publications. Her investigation into the South Side is in great part informed by her reporting skills. She brings history, politics, economics, and culture to bear explaining the who, what, where, when and how of the South Side of Chicago. Starting with a clear-eyed look at the terrible history of racism in the city, Moore examines housing policy and practice. She describes red-lining, economic exploitation based on race, and the myriad of failure of the Chicago Housing Authority. Moore anchors housing in the local histories of neighborhoods unable to shake free from poverty. It is a story of generations trapped.

Moore is a journalist. She reports on the South Side for WBEZ, Chicago’s NPR station. She has covered other cities and other countries. Her writing is in newspapers and national publications. Her investigation into the South Side is in great part informed by her reporting skills. She brings history, politics, economics, and culture to bear explaining the who, what, where, when and how of the South Side of Chicago. Starting with a clear-eyed look at the terrible history of racism in the city, Moore examines housing policy and practice. She describes red-lining, economic exploitation based on race, and the myriad of failure of the Chicago Housing Authority. Moore anchors housing in the local histories of neighborhoods unable to shake free from poverty. It is a story of generations trapped.

Training her eyes on Chicago’s public schools, Moore paints an equally chilling picture of segregation. Chicago actively resisted calls and judgments to integrate its school system, despite marches and protests and well-meaning pressure from progressives of all stripes. Her chapter on CPS is titled “Separate and Still Unequal.” Class matters, too, and Moore is equally sharp when looking at grocery stores, food stores and restaurants across the city. On one level, her book is a study of the effects of systemic racism.

The South Side is more than a work of journalism, however. Moore is no embed reporting to a distant and curious public. She is fiercely proud of her city. She loves the South Side, warts and all, and wants readers to understand and appreciate it. A resentment to those that would demean it givers her prose attitude and passion.

Moore grew up in Chatham, an African-American neighborhood that had been an Italian, Hungarian and Irish neighborhood in earlier decades. After World War II the whites moved out and black families moved in. Chatham provided a solid foundation for Moore’s childhood and she found a home in Sutherland, an integrated CPS elementary school in nearby Beverly. For high school, she attended Morgan Park HS, which was known for its college preparatory program. When Moore was a student it was mostly black, with white and Hispanic students. (Today it is 97% black – segregation in schools for much of the city has significantly increased). Moore looks back on her high school education fondly and is proud to call herself a product of CPS.

She rails against the violence in the city – and is equally angered at those who label the city with a broad brush of little but racism, crime and despair. Fear is increasing, she writes, even as overall rates of homicide, measured not year to year but over the long-term, is down. Moore wants policy discussions about violence to be guided by facts, not emotion. She sees the underlying economic problems and high levels of unemployment as the real issue. Looking to leaders like Harold Washington, Moore believes that Chicago can build political coalitions to push back against racism and segregation.

Moore works to end her book on a positive note. She talks with activists, academics, artists and legislators, arguing that change is possible.

Don’t read The South Side to look for policy suggestions. Don’t study it expecting an agenda for future mayors and aldermen. Instead, Moore wants us to reconsider, reappraise and appreciate the South Side. She tackled the task with integrity and care.

David Potash