Urban Love Letter

How does one “know” a city? Can we even make sense of a metropolis? William James called a baby’s first experiences in the world to be a “blooming buzzing confusion” and I think that it’s an apt description of trying to take in the fullness of a city. It’s an overwhelming task. To find connection and meaning in an urban setting, we blinker our sensations, using moments, glances, and focus. A building represents a neighborhood, a person stands for a type, and an exchange can reflect something greater.

One of my favorite genres of writing comes from the ambitious author who tries to capture a feel, a slice, a perspective on a city through literary non-fiction. The flaneurs of 19th century France are well-known examples, but they exist in other times and places, too: Pliny the Younger on Rome, Pepys on London, Balzac on Paris, and Dreiser on Chicago are part of this tradition. They produce journalism that is written with the care and creativity of fiction. They are our best explainers of urban life. And to their ranks, I recommend adding Suketu Mehta on Bombay.

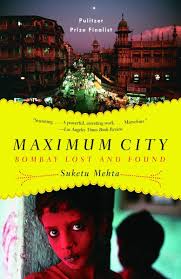

Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found is Mehta’s 2004 love letter to Bombay. Now known at Mumbai, the city has had many names, Mehta tells us. It truly is an overwhelming metropolis. The scale and scope of the Bombay is staggering: 18.4 million people in 2011 and it is India’s largest, and densest, city. Mehta was born in Bombay and left for the US at the start of high school. He was educated in America, became a writer (fiction, nonfiction and screenplays), and returned to Bombay in his mid-30s with a family. He spent more than two years there, investigating the city and its seedier underbelly, interviewing gangsters, policemen, actors, producers, and a host of men and women about town. It’s something akin to Luc Sante’s Lowlife but for India. Maximum City is a fascinating read.

Mehta talks with the poor and the super wealthy, with poets and merchants, with cooks and gourmands. His curiosity and willingness to listen is extraordinary. It’s clear that tons of research went into Maximum City, including dangerous interactions with killers and other criminals. Mehta is unsparing in his accounts of the corruption, incompetence and indifference of the city. And yet – and it’s an important “yet” – he loves the city and its people. There’s great warmth and compassion in his writing.

Maximum City is not a travel book. I’m sure, too, that boosters and realtors hate it. But for those of us who have not been to Mumbai/Bombay and are curious, for those of us who find ourselves drawn to cities and city life, it is a book well worth our time.

David Potash