Shantyboats Aren’t On The Grid

Opening a book like Harlan Hubbard’s Shantyboat: A River Way of Life is akin to wandering into a new world. Eye-opening does not begin to cover it, for Hubbard’s book is an extraordinarily provocative exercise in doing and thinking differently. The book, and the Hubbards, truly caught me by surprise. The more that you learn about them, the more interesting they become.

Hubbard (1900 – 1988) was born in Kentucky. His mother moved him to New York City when he was a child, after the death of his father. He attended art school and after World War I, design school in Cincinnati. Hubbard and his mom returned to Kentucky, where he held a number of jobs while becoming increasingly critical of modern culture. In 1943 he married Anna Eikenhout (1902 – 1986), a librarian. Anna, an Ohio State honors graduate, spoke several languages and was an excellent pianist. Together the Hubbards did something that many of us talk about but very few ever achieve: fashion a life together on their own terms.

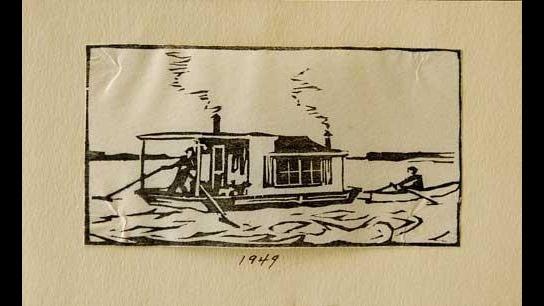

The couple built a shantyboat in Brent, Kentucky, on the banks of the Ohio River upstream from Cincinnati, in the fall of 1944. A shantyboat is a small, simple houseboat, something that can be put together and repaired easily by someone good with tools. It is a craft for drifting, not for speedy travel. The Hubbards moved into the rough structure, and nearby tent, almost immediately. It took about two years to make the craft ready for the water. They then floated down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, reaching New Orleans in 1950. Shantyboat is Harlan’s account of the trip, brightened with his illustrations. Published in 1953, the book became something of an underground classic. Hubbard followed up with several other books, as well as a lifetime of making art.

The book does not argue for organic living, avoiding capitalism or the dangers of working for another. It is not a treatise and nor does Harlan complain about modernity. Instead, it is a most direct and straightforward account of how the Hubbards went about their six-year journey. Hubbard explains how they put the boat together, the decisions they made about heating, storage, windows and all the other details that called for attention. If you have to find firewood to burn to stay warm, priorities change. Eating, not surprisingly, takes up much of the couple’s time, for they did not have much money and they did not want a lifestyle that required regular shopping. They grew vegetables, foraged, fished and traded, all with quiet good cheer. If they ever went hungry, it did not appear in the narrative. They always found a way and found ways, too, to help those they met along the way. The community of people they encountered, on and around the river, were supportive and welcoming.

Details give the book a tremendous tangible texture. I didn’t know that groundnuts would make a good alternative to potatoes, or various types of catching river fish. Shantytown is studded with hands-on experience and words of wisdom. Harlan could have given more maps, charts and diagrams. It is that interesting. He is a patient guide, too, for he is up front about learning from others. While it might seem to be a solitary way to live, there were always opportunities and reasons to interact with others.

The boat drifted, which meant there had to be constant attention to where and how the boat was situated. Paying attention to traffic on the river, who was going where and why, was essential. The Hubbards were far from the only people living along the river, either. They met many different characters, found places to stay for extended periods (helped with their farming), and they lived in community while somewhat apart from traditional society. Harlan painted, they wrote, they read, they made music and stayed very busy, with dogs, bees and an endless series of adventures.

One might be tempted to think of their journey as a way of leading a “simple” or “leisurely” life, but that would be far from the truth. Their day-to-day was very full and rich with experience. Who is to say it is better or worse than anyone else’s?

The couple returned to Kentucky and purchased land by the river. Their spot, Payne Hollow, grew over the years. It was a physical expression of the couple’s values and lifestyle. Payne Hollow was their home until their deaths. They had no electricity, no motors and no engines. The Hubbards had their own environmental commitments. Their food never came from a supermarket. A bicycle got them to a local town, when needed. They were quiet, enjoying what each day brought, and it was often visitors. In fact, they became minor celebrities in Kentucky. PBS did a show about them, and Harlan’s art was appreciated and purchased by many.

Shantyboat and the Hubbards are, in a word, inspirational.

David Potash