Puerto Rican Crisis, Heroism, and Food

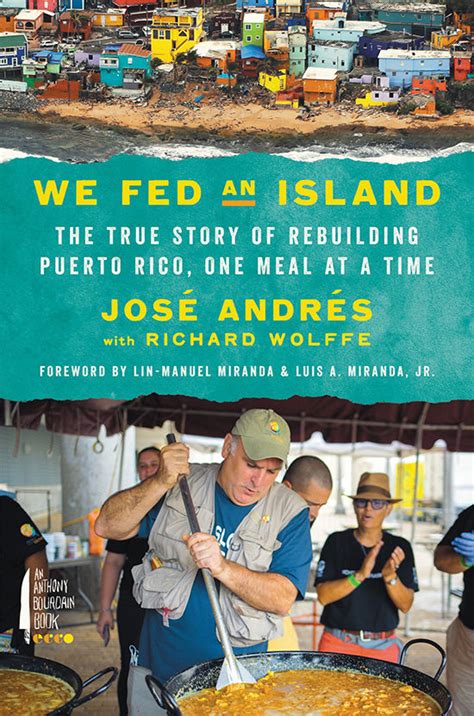

Hurricane Maria caused tremendous destruction in Puerto Rica in 2017, killing thousands and wiping out much of the island’s infrastructure. It was a disaster in the true sense of the term. A few days after the storm subsided, Jose Andres, an internationally renowned chef who had a restaurant in Puerto Rico (among several others), decided that he was going to make an effort to help. He recounts his efforts, filled with successes, failures and challenges, in We Fed an Island: The True Story of Rebuilding Puerto Rico, One Meal at a Time. It’s a cheering, frustrating, and interesting read – and not for the reasons that I expected. I did not know what a relief efforts was like for the key volunteer organizations. While I imagined confusion and difficulties, Andres’s book offers a more complete level of understanding – and highlights the consequences of poor leadership. The people of Puerto Rico were not adequately supported after Maria.

Andres is a chef, writer, television personality, and humanitarian – a man of influence and ability. In 2010 following a crisis in Haiti, he created a non-profit, World Central Kitchen (WCK), to feed people after disasters. He’s received numerous awards and by every standard, is wildly successful. As you might imagine from such a profile, he is also comfortable expressing himself. He is not a scholar; he is focused on outcomes. We Fed an Island captures all of this: incredible generosity, a tremendous ability to get things done, great smarts and a perspective that is about goal setting and achievement. It is a first-person account through and through. If you are looking for a more comprehensive study of the disaster, this is not the study. And while this book would have been stronger with more structure and data, that was not the aim. I have nothing but respect for Andres and gratitude for his work and the book. Proceeds from the book go to WCK, too.

For people to survive and rebuild after a hurricane, many things have to happen, from health care to water to power to shelter. Andres arrived and focused on one of the most basic needs: getting people enough food to get by. He drew on his experience with WCK and other relief efforts, as well as deep connections to many on the island, from former co-workers to elected officials to media personalities. Andres’ team quickly established kitchens and then, fighting a host of indifferent or ineffective bureaucracies along the way, greatly expanded its reach. It took time, but eventually other organizations stepped up as well. All though Andres’ was not the only group providing food, it is not far off from asserting that they truly did “feed an island”

The book is peppered with wisdom about relief efforts, problem solving of all shapes and sizes, and how restaurants work. “When you cook at scale, you become expert at processes” Andres tells us – and much of the book is all about process thinking. It’s also about how knowing your customer and community, which can make all the difference. Reading about the many different kinds of sancocho Andres’ team prepared was cheering and also made me hungry. Good Puerto Rican food is very, very good and a good sancocho is fantastic. Andres cares a great deal about the food, its impact, and even explains how customers can become volunteers. The big picture realization is the many ways that thoughtful and caring relief work can bind a community.

Much of the book, though, is about the challenges. Above and beyond the difficulties that Puerto Ricans faced, Andres and his team faced many, most visible of whom was President Trump and other elected and appointed officials. Andres does not hold back his criticisms. Particularly galling, but not surprising, are the recurring gaps between what was happening and what was reported. There was a massive lack of coordinated leadership in the relief work, regardless of what was reported.

Through a different lens, We Fed an Island is a call for reform. It is essential. We need to rethink our disaster relief organization and processes. Without that, the next crisis could be worse. Andres is worthy of our thanks – for his work, his food, and his willingness to share.

David Potash