Women in Occupied Paris

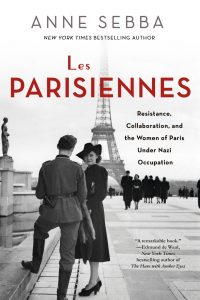

Les Parisiennes, by Anne Sebba, examines at the lives of women in Paris from the late 1930s, through WWII and the Nazi occupation, until after France regained autonomy. More historical journalism than a traditional work of history , the book attempts to capture the wide range of experiences of women in this period of crisis and change. It’s an ambitious endeavor. Sebba has consulted memoirs, biographies, the popular press, and, occasionally, primary sources from everyday women in Paris. However, so much happened to so many over the 15 years that simple or even consistent characterizations are very difficult. It’s an extraordinarily interesting time – a period of drama and heartbreak, as well as heroism – and Sebba does a fine job capturing the period’s complexities.

Les Parisiennes, by Anne Sebba, examines at the lives of women in Paris from the late 1930s, through WWII and the Nazi occupation, until after France regained autonomy. More historical journalism than a traditional work of history , the book attempts to capture the wide range of experiences of women in this period of crisis and change. It’s an ambitious endeavor. Sebba has consulted memoirs, biographies, the popular press, and, occasionally, primary sources from everyday women in Paris. However, so much happened to so many over the 15 years that simple or even consistent characterizations are very difficult. It’s an extraordinarily interesting time – a period of drama and heartbreak, as well as heroism – and Sebba does a fine job capturing the period’s complexities.

Most of us are not historical actors. Rather, our lives are shaped by history. Sebba gets this. The key battles of World War II were not fought in Paris. However, the war’s violence – and in particular, its violence against Jews – took place throughout the city. It was a battlefield of a difference sort. Sebba gives the reader a better understanding of the interplay of individual women’s lives and the moral ambiguity of life under occupation. Questions of honor, collaboration, and agency were all played by women and on women, literally and symbolically. I think that Sebba could have advanced a more explicit feminist argument – it would have sharpened her narrative – but her interest is in the person.

Sebba is attuned to the horrors of the war. She examines its impact on her subjects, writing with compassion and imagination. She is a skilled writer.

Sebba, also, is aware of the difficulties inherent in her approach. She seems of two minds, sometimes giving more focus to the political. Other times she is more keen on the personal. In fact, there are two subtitles to the book: Resistance, Collaboration, and the Women of Paris Under Nazi Occupation is one and the other is How the Women of Paris Lived, Loved, and Died Under Nazi Occupation. The former is more historical and the second is more biographic.

Haunting Les Parisiennes are questions of why: why did some women collaborate and others resist? Why did some women risk their lives to protect Jews and others were fine profiting from anti-Antisemitism? These questions are difficult and they defy simple explanation. Read collectively, they speak to the deep challenges of everyday life in the occupation.

The lives Sebba has unearthed are extraordinary. The war was a cauldron for choice – one could not simply “live” and get by. Basic survival demanded extreme behavior. With or without broader analysis, the individual stories make for fascinating reading. Les Parisiennes offers a valuable perspective to understand the complex tragedy that was World War II.

David Potash