Seeing Through Myths and Stories

Nesrine Malik is a London-based journalist who writes for The Guardian and presents on the BBC. Born in the Sudan, Malik spent most of her early years in the mid-east before moving to the UK. She writes about contemporary politics, especially in the U.S. and England, Islam, and identity politics. Malik is very smart and unapologetic in her critiques. She provides a vital perspective, informed by her personal history.

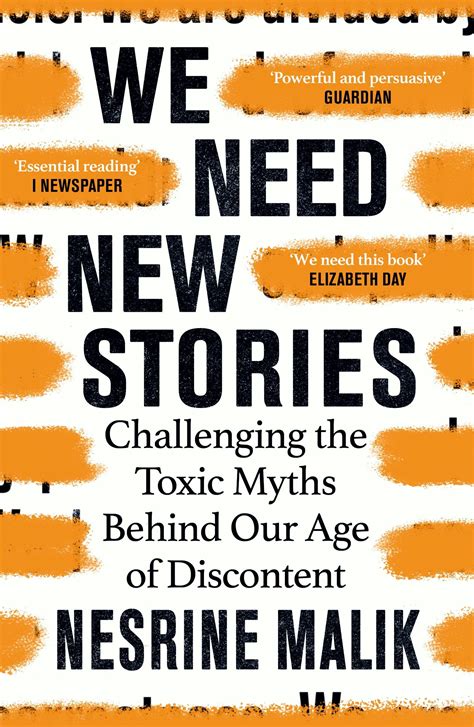

Right before the pandemic, Malik’s book, We Need New Stories: The Myths That Subvert Freedom, was published. It is a short, accessible and thoughtful presentation of six “myths: that frame US/UK political culture. Do not think of Joseph Campbell. Instead, conjure up what everyone knows to be true but turns out is not, actually, true. Malik efficiently assesses and critiques these myths, or commonly accepted “truths”, as most definitely creative fictions. They are lies or misunderstandings with a purpose and impact. She effectively argues in the book that the myths stand in the way of human freedom.

Malik’s focus, accordingly, is not on just on using data to demonstrate what is and is not accurate. She is after something slightly different, the effect of mindset when it comes to how important big picture political issues are framed. The six myths Malik calls out are the myth of the reliable narrator, political correctness, a free speech crisis, harmful identity politics, national exceptionalism and gender equality. The terrain is all contemporary. Each chapter, though, provides some reference as each of these have lengthy and complicated historical roots. Woven throughout the exposition are examples and observations drawn from Malik’s personal history as an Islamic woman growing up in the Sudan. She sees things that many of us who have lived in the culture might not recognize.

For each of the myths, Malik presents data, resources and examples to illustrate the fundamental unsoundness of the commonly accepted story. The reliable narrators in the past two decades, for example, reliably get many things wrong and rarely apologize. She examines here the “wise leaders” who preach a particular course of action and the preeminent example is the invasion of Iraq. Untold numbers died, billions were expended, and accountability never really happened. In fact, the same leaders and leadership structures remain as influential today. Our narrators, in other words, need to be questioned. Malik’s argument is compelling. When it comes to political correctness and a crisis of free speech, Malik emphasizes that what is different today is that those with power and influence are peddling these issues for gain. Are we truly in a crisis where many are afraid to speak honestly because of the heavy weight of political correctness? Malik underscores the recurring strategy of creating a sense of victimhood to motivate identity and political action. Exactly who is being harmed and how when people celebrate their identities? Or interrogate stories of national exceptionalism?

The book is interesting, well-paced and solid. Malik delivers her claims effectively. Missing are discussions of why these myths are so prevalent and exist across countries, cultures and histories. She does not give much energy into exploring why these myths are so successful. In the marketplace of ideas and arguments, why does an imagined fear of political correctness have legs while other fears and issues do not? Malik hints at reasons, but does not travel that path. It is unfortunate, for many of her exploded myths tightly align with decades of provocative scholarship on nationalism. Stories of injustice and victim hood are effective tools at mobilizing political support and agency in some circumstances. It is key to remember, too, that victims are rarely asked to think of anything or anything other than themselves. Perhaps in another book.

I am looking forward to reading more from Nesrine Malik. We need her insights and perspective.

David Potash