Mead and a Mighty Read

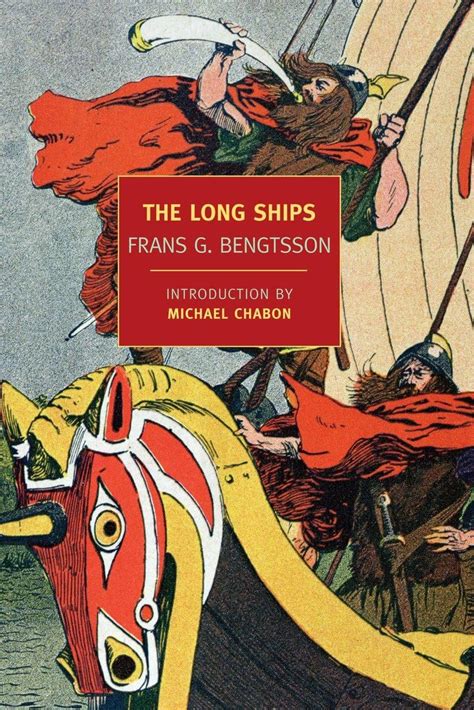

The Long Ships is an brilliant saga, extremely entertaining, delightfully amoral, anachronistic and surprisingly funny for all its gore and death. Written in two parts in the 1940s by Frans G. Bengtsson, the book quickly became popular in Swedish literature. Reissued by the New York Review of Books in a translation from Michael Meyer, it is a 20th century classic, an adventure for the ages.

The book tells us tales of Red Orm, an imaginary Viking, and his exploits from roughly 980 AD – 1010 AD. The son of a chief, Orm is kidnapped as a youth from Skania (now southern Sweden). He becomes a slave in Andalusia, fights his way to freedom, and engages in all manner of adventure and conflict as he travels through much of Europe before making his way home. There are friendships, family drama, battles, losses, victories and love. Enough takes places for multiple seasons of a cable drama. While it may sound like any number of epics, The Long Ships is something special.

Bengtsson based his plot points on historical examples and the research shows. The goal, though, is not veracity or scholarship. Instead, the author wants to tell us stories grounded in care and literality. What makes the book work is how Bengtsson tells the story: think old-school prose with a soupcon of modern awareness. No internal dialogue graces the pages. The characters are clearly drawn and their actions – and words – speed the text. Wants and desires are clear. Everything is extraordinarily straightforward and direct. When a character is conflicted, their condition is spelled out. Our characters are pragmatic and relatable, even though they are living and struggling in a violent world. Bengtsson does not romanticize the Vikings. Life could be brutal. There’s a tremendous linear quality to the book, a trait that makes one yearn for straightforwardness in our day-to-day.

This is not to say that characters in The Long Ships do not engage with difficult questions. They often wrestle with all manner of problems and issues. The book is situated as the Vikings’ dominance shifted to something different – perhaps more civilized, as the Catholic Church would frame it? The theme of religion is frequently explored. Red Orm became Muslim simply to stay alive, and later he decides to become a Christian. They were, after all, sometimes luckier. Some characters convert and others do not, and there are multiple points of view about why to, or why not, to do so. Bengtsson very much appreciates the context that frames these themes. The Viking tradition of raiding, after all, is a less than moral activity. It is violent and awful. Our heroes are ne’er-do-wells, often blessed with a dry sense of humor. Males drive the action, yet female characters are central to the story. How do people live and make choices in such world? Bengtsson’s world gives us a sense of how some might be and act. While assessing its historical accuracy is best left to experts, for the reader, it rings as true.

The Long Ships stands out as engaging and epic as Tolkien without taking itself too seriously. It is a mighty good read. As Michael Chabon puts it in his introduction, the novel “stands ready . . . to bring lasting pleasure to every single human being on the face of the earth.”

David Potash