Safety and Feeling Safe

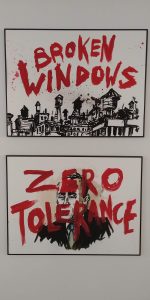

In September in New York City, I spent time at the Museum of Broken Windows. An eight-day “pop-up” event in the Village, close to NYU, the Museum of Broken Windows was organized by the New York Civil Liberties Union as a critique to the broken windows theory of policing. The concept – that crime was more likely to happen in an environment that looked untended – was part of the early 1980s zeitgeist. It was in the popular media and in politicians’ rhetoric. It aligned with the “law and order” emphasis of President Reagan. It also resonated with those fearful from urban crime and resenting the major urban disinvestments of the 1970s. In other words, just about everyone bought into it.

In September in New York City, I spent time at the Museum of Broken Windows. An eight-day “pop-up” event in the Village, close to NYU, the Museum of Broken Windows was organized by the New York Civil Liberties Union as a critique to the broken windows theory of policing. The concept – that crime was more likely to happen in an environment that looked untended – was part of the early 1980s zeitgeist. It was in the popular media and in politicians’ rhetoric. It aligned with the “law and order” emphasis of President Reagan. It also resonated with those fearful from urban crime and resenting the major urban disinvestments of the 1970s. In other words, just about everyone bought into it.

The show was packed when I attended. The crowd, mostly young people, was focused and noisy. There content was more images than text, more art than explanation.

The point of the exhibit was to showcase the ineffectiveness of broken window policing, emphasizing that it criminalizes those of color and less means. The show referenced a major report by the New York City Police Department on “quality of life” crimes and policing, which proved that arrests for these minor infractions does not actually reduce crime. Incomplete and passionate, the museum was about energizing and raising awareness. But of what? The issue is not just about policing. Much more is going on with this dynamic.

Mulling this over in the past few weeks, I’ve been wondering: why did the theory of broken windows become so popular? What is it about stoking up fears that is so effective? I realized – probably belatedly – that as long as I’ve been alive, there have always been a drumbeat of fears, threats and crises being pressed by leaders and the media. We have been, supposedly, under continuous threat since forever. In my 55 years, it’s been the Soviet Union, the communists, then urban crime, then crack, then terrorists and more terrorists. And that’s just the high level threats. Greater access to information, through the media and the internet, has not just been about more information. It is, in great part, also about more threats and threats on top of those threats.

The world is a scary place. We all know that. However, some threats spur more action than others – often without research or deep consideration. When threats align with interests and what we, as a people, want to believe, then there is change. We take action, often quickly, to calm ourselves and assert our power. Collectively would be doing better if we had more judgment and prudence when it comes to what frightens us and why.

It’s an opportune moment for all us to take a harder look at what we are hearing and seeing as threats. Let’s stay prudent and not live scared. A November resolution?

David Potash