Suffrage Drama in Tennessee

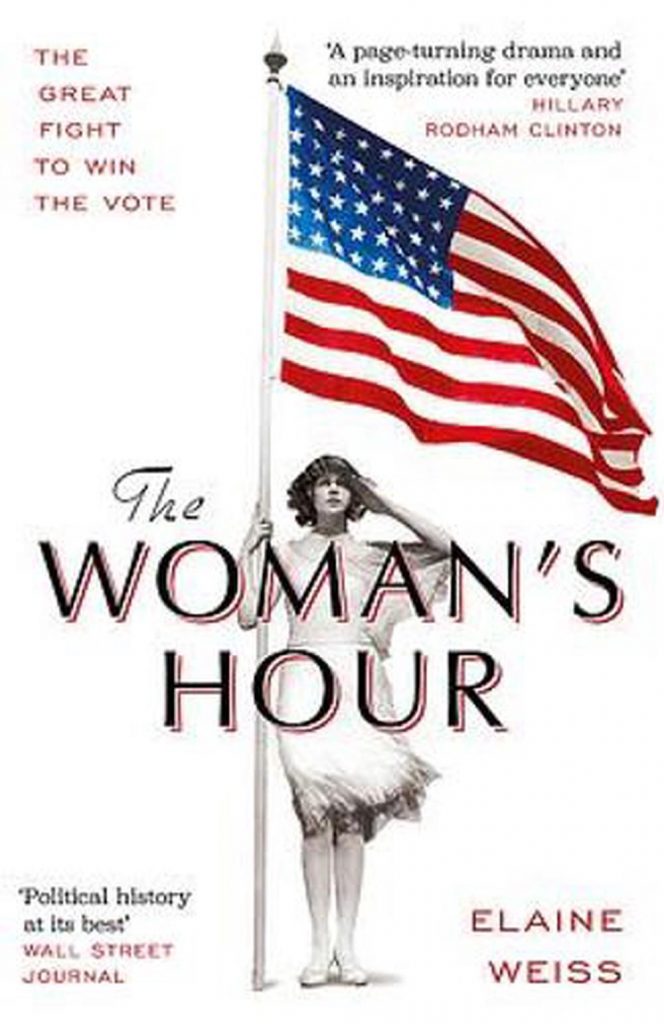

The expansion of American democracy is often referenced as inevitable and unidirectional. However, anyone who takes a close look at history knows that nothing could be further from the truth. Political change is messy. That is particularly true when looking at the ratification of the 19th Amendment in Tennessee, the final state to make women’s voting part of the US Constitution. It’s a complex story and the focus of Elaine Weiss’s work of nonfiction, The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote.

Weiss, a successful journalist, brings a journalist’s perspective to the task at hand. Questions of who, what, when and how drive the book. She is very strong when it comes to the people in Tennessee involved in the summer 1920 battle at the state capitol. Weiss paints detailed pictures of the players: Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association and head of the “Suffs,” Josephine Pearson, leader of the Tennessee State Association Opposed to Women’s Suffrage and head of the “Antis,” their key followers, and many elected officials, ranging from state legislators to President Wilson and future President Harding. Weiss’s attention to personal detail emphasizes the contingency of struggle. Ultimately it was determined by an extremely close vote in the state legislature. The sausage making included hard-pressed lobbying, shifting alliances, threats and conspiracies, and crafty parliamentary maneuvers. Even though we know the eventual result, Weiss’s skill renders the action dramatic and engaging. It makes for entertaining reading. It is clear why the book has been optioned for a film.

If you do pick it up, I encourage reading more widely about the topic. The historian and the teacher in me want to stress that while the study of individuals and their behavior in specific events can be fascinating, broader understanding is possible when we also consider continuities, changes and context. It was a period of profound change and great conflicts. For example, the promotion of white democratic principles, as championed by President Wilson, had an international impact as well as one in the American South. Wilson, along with almost all of the elected officials in Tennessee, was steadfastly opposed of Black women voting. That is but one of the issues in the story that is essential towards knowing how and why the vote played out the way it did.

Another important realization from The Woman’s Hour is that history is framed and written by those that are successful. It’s a truism that is worth repeating and re-emphasizing. The change of one or two votes, establishing a majority, can be extremely powerful in the casting of a historical decision. Was Tennessee all that more democratic (with a lower case “d”) than Maryland, which voted against ratification? Giving historical change close attention, as Weiss effectively does in this book, often clarifies and complicates history. And that, by my account, is very much to the good.

David Potash