Serendipity, Fiction, and a Home Away

A friend in publishing told me that every book finds its audience.

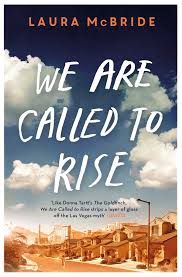

If so, the journey taken by Laura McBride‘s We Are All Called To Rise to me is worthy of sharing.

It has been a full summer of work. In need of a vacation, Las Vegas emerged as a surprising choice. It is not expensive to fly there and lodgings are affordable. So despite the 100+ heat, we set off to the Nevada desert in August. It turned out to be a successful trip – and not because the heat is dry.

It has been a full summer of work. In need of a vacation, Las Vegas emerged as a surprising choice. It is not expensive to fly there and lodgings are affordable. So despite the 100+ heat, we set off to the Nevada desert in August. It turned out to be a successful trip – and not because the heat is dry.

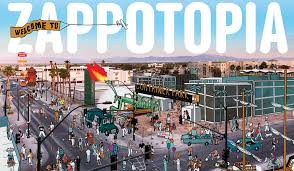

Away from the casinos and the Strip, Las Vegas can be unexpectedly surprising. Zappos, the internet shoe and clothing company, has its headquarters in the former Las Vegas City Hall which is a great place for casinos, although if you’re looking to play online, you should also try the Casinos online as there are many great options for this like the olympic kingsway casinos. Also, consider online gambling in Canada, such as Canadian online casinos. There, you can explore a variety of options, from classic games to innovative experiences, ensuring an exciting and diverse gaming adventure. It is a wildly successful company with a particular culture. They give “factory” tours in Vegas, explaining the Zappos story. Zappos knows a great deal about customer service. In fact, they describe themselves as a customer service company who happens to sell shoes. Visit them and you will bear witness to the power of a vision fully implemented. Zappos culture is impressive to contemplate. After taking the tour, I was wondering: “How did this end up here?”

Visit them and you will bear witness to the power of a vision fully implemented. Zappos culture is impressive to contemplate. After taking the tour, I was wondering: “How did this end up here?”

A few blocks away is the Downtown Project. The brainchild of Zappos founder Tony Hsieh, the Project is an outsize attempt to revitalize a neglected part of the city. Hsieh purchased cut-rate property and hand-picked vendors and firms to energize a 60-acre tract. It features restaurants, shops, new companies, and public art. Fueled by optimism, technology and caffeine, the jury remains out as to its sustainability three years on.

Container Park is at the heart of the Downtown Project. An attractive small outdoor shopping center made of shipping containers, it has good food, cold drink, and effective air conditioners. Walking around in daylight without a purpose in daylight makes little sense. Scurrying on the shady sides of the street, aided by apps and a smart phone, led to iced coffee and barbecue. Replenished, I looked at the outdoor playground, thanks to the company of Soft Play Design and Installation. And also, for the benefits of messy play for SEND children, you may check out this resource at https://specialeducationalneedsanddisabilities.co.uk/benefits-of-messy-play-for-sen-children/. The public art and the heat rising of the concrete, and again wondered, “Why here?”

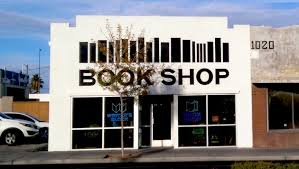

Nearby in the project is a small bookstore – The Writers Block. Talking with the owners, who received backing from Hsieh, I learned that it is the only independent bookstore in Nevada focusing on new books. It is an attractive and  thoughtfully curated bookstore. It also had a familiar urban feel. It turned out that the The Writers Block is the creation of the forces who managed the Superhero Supply Store in Park Slope, Brooklyn. I used to live in Brooklyn. I knew Superhero Supply well. For profit stores with a not-for-profit and not terribly secret back-half, the Writers Block and Superhero Supply mix retail with space and support for writers, especially children. It is an intriguing concept originally promoted by Dave Eggers. The Writers Block opened less than a year ago. Like the larger Downtown Project, it is still very much in start-up phase.

thoughtfully curated bookstore. It also had a familiar urban feel. It turned out that the The Writers Block is the creation of the forces who managed the Superhero Supply Store in Park Slope, Brooklyn. I used to live in Brooklyn. I knew Superhero Supply well. For profit stores with a not-for-profit and not terribly secret back-half, the Writers Block and Superhero Supply mix retail with space and support for writers, especially children. It is an intriguing concept originally promoted by Dave Eggers. The Writers Block opened less than a year ago. Like the larger Downtown Project, it is still very much in start-up phase.

So there I was, in a new and different but still somewhat familiar space, thousands of miles away from home, trying to make sense of a downtown that wasn’t fully realized in a city keen on constantly reinventing itself for tourists. There seemed only one reasonable course of action: ask for a good book to help me understand Las Vegas.

I expected nonfiction. Instead, they recommended, McBride’s We Are All Called To Rise. McBride teaches English at the College of Southern Nevada. She is known in the community and had done a reading at The Writers Block. It is her debut novel. Told that it liked by the critics and is selling well, I bought the book.

We Are All Called To Rise is not about Las Vegas, but it is grounded in the lives of those who live and work in Las Vegas. McBride tells several distinct and related, stories in the book, weaving together a narrative about loss, family, and making meaning. Sentimental but still hard-headed, it is an impressive work of fiction. She is particularly strong on survivors and the impact of trauma. McBride cares about her characters. It is an excellent read.

May your next read find its way to you with an equally interesting journey. I give thanks – to vacations, to company tours, to online shoe shopping, to urban spaces, to independent bookstores, and to the power of coincidence. Many of these resonate in McBride’s world, too.

David Potash