In the Belly of a Beast of a Beast

Greater than day-to-day reporting, outstanding journalism can carry with it the creativity of literature and the power of the truth. It does not come easily – demanding talent, skill, commitment and courage.

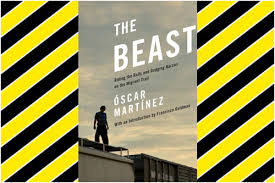

Oscar Martinez is an El Salvadorean journalist who writes for Elfaro.net, an online Latin American newspaper. It is an informative, vibrant site that offers insight and news into a region that is often under-reported and poorly understood. It’s a good place to learn and explore.

Martinez parlayed his reporting into an outstanding book, The Beast. It is a fearless study of the migration of people’s from Latin America to El Norte, the U.S., through a focus on “La Bestia” – the freight train that runs through Latin America. Much of the content was in a series of articles penned by Martinez. The book is more, though, and taken as a whole it portrays a harrowing region and movement of peoples. There is a great heroism, compassion and care here. Also, there is horrific violence, cruelty, greed and indifference. Beautifully written and close to its subjects and their accounts, The Beast is difficult to read. The stories are that tough.

The book came out in Spain in 2010, in Mexico in 2012, and in the US – and English – a few years later. It won awards and praise. Martinez interviewed migrants, families, travelers, the police and gang members. He helps the reader understand the difference between fleeing and migrating – and also the hard choices people must make. Kidnapping, theft, rape and exploitation are rampant. The normal structures of civil society have been bought off or threatened into inactivity. The crimes, desperation and migratory patterns have developed over so many years that they collectively have become something of a “system” – and with their establishment, ever greater resistance to reform or improvement. The system itself is an indifferent beast.

Martinez writes from a perspective that every life has value, that every life matters. The Beast explores a world based on an antithetical view: life is nasty, brutish and short – and no one individual matters all that much. It is an ugly, frightening picture. It’s all the more damning because economic and political actions by the US are active contributors. Governments have been destabilized and the growth of the drug cartels has been fueled in part by American markets. Reading this book gives insight into why so many are fleeing Central American.

The book is driven by outrage, but this is no polemic. The Beast gives voice to the powerless and mostly stereotyped immigrants. Martinez cares about them and their plight – and makes the reader care, too.

David Potash