One of the iconic figures from Paris in the 1800s is the flaneur, a man of leisure who wanders through the city, observing and writing. Flaneurs have been linked to modernism, in particular a sense of simultaneous engagement and alienation, and above all, with the city. They are our historical experts in describing the day-to-day as well as the profound, making sense of the complexities of urban life in the nineteenth century.

What does one do today with the American suburbs? Who can explain these strange spaces?

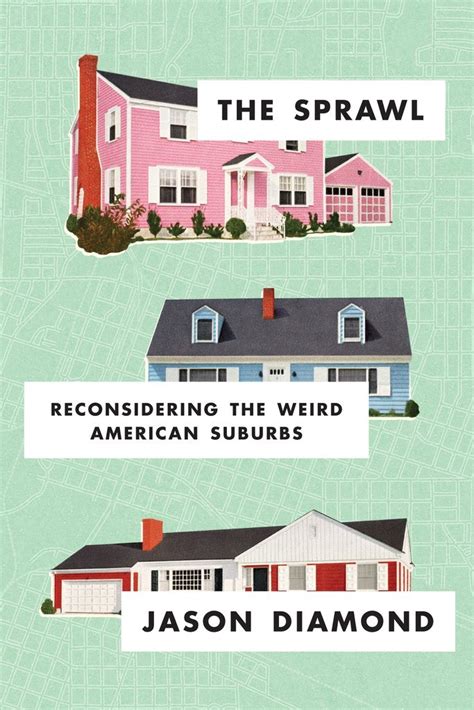

Those questions circled around my reading of Jason Diamond’s The Sprawl: Reconsidering The Weird American Suburbs. Diamond, now a denizen of Brooklyn, is a product of the Chicago suburbs. He is a journalist, critic, writer and modern day flaneur. The Sprawl is a thoroughly researched yet idiosyncratic wander through America’s suburbs, a road trip across the country as well as down memory lane. Neither history nor social science, the book is a very interesting meditation on sprawl through the eyes of a very well-informed critic.

There’s history and some facts in The Sprawl, but Diamond’s primary vehicle of understanding is popular culture. Want to understand the Chicago suburbs? He would give us the movies of John Hughes, as well as reference indie rock and Wayne’s World. While I’m reasonably up on many of his references, Diamond’s knowledge is encyclopedic and deep. He spins a network of popular culture to map the burbs. Woven throughout the book are Diamond’s personal recollections, his personal history, and his predilections. He comes across as a very interesting person, a pleasant and curious guy who writes very well.

Are American suburbs all that strange? Sprawl – America’s suburbs and exurbs – are by definition spaces defined by what they are not. They are neither rural nor urban. They are not small towns. Sprawl is the space around and in between, the plazas, roads, highways and byways between shopping plazas and housing developments. It is easy to get lost, physically and in terms of meaning, when the only available markers are negatives. Diamond’s challenge is that what he is looking at is everywhere and nowhere.

Despite the constraints, Diamond tells a good story. The Sprawl rightly received several awards. It is not a map, but this book is most certainly an entertaining and informative guide.

David Potash