Settler Progressivism and the Antipodes

History, thankfully, is never finished. While the contours and highlights of a period might be readily agreed upon, questions of causality and correlation can remain contentious. Sorting out why something happened is often extremely difficult. A well-crafted argument, from a different viewpoint, will inevitably foster new thinking and raise new queries.

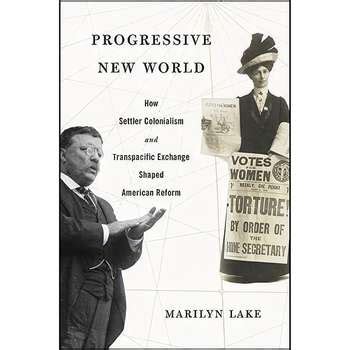

Australian historian Marilyn Lake has done just that in an outstanding work, Progressive New World: How Settler Colonialism and Transpacific Exchange Shaped American Reform. Lake is a professor of history at the University of Melbourne and an indefatigable researcher, spending years in America on this book. Starting from a less considered perspective – how did Australian reformers interact and influence American thought leaders in the Progressive Era – Lake paints a fascinating picture of mutual admiration through decades of robust exchange. The book, though, is about much more than a back and forth of people and ideas. Lake fashions a strong claim for the centrality of Whiteness as an organizing principle of multiple strains of “reform.”

The book opens with a prehistory of progressivism, grounded in elite responses to the major economic and social transformations in Australia and the United States. The intersections are fascinating and telling. In the 1870s Charles Pearson, an English historian of the Middle Ages who had a farm in South Australia, wrote National Life and Character: A Forecast, spelling out how White colonialism could effectively reshape the nation. Pearson was friends with Harvard historian Charles Eliot Norton, whose cousin, Francis Parkman, wrote extensively about the American frontier. Harvard-educated Theodore Roosevelt, before he became president, was an active writer who favorably reviewed Pearson’s book, locating it within the larger context of settler colonial advancement. Lake shows how these thinkers and leaders aligned progress with White democracy, White manhood, and self-government through a particular strain of state action. Indigenous peoples, the argument ran, lacked the character and self-discipline necessary for democracy and self-determination. These claims would play out over the decades in the American west, Hawaii, the Philippines, Cuba – literally all over the world. Elite institutions and networking, as Lake meticulously documents, facilitated the mutual group-think and collective action.

The allure of the frontier, hardy White men taming the elements and creating new social structures, appealed immensely to many of these thinkers. There were many of elites who embraced the conceit, too, as Lake’s list of elite thinkers who wrote to each other, visited each other, and supported each other is extensive. Part of the book are what akin to a late 1800s Who’s Who, with Harvard connections at the core. As they traveled the United States and Australia, these reformers wrote extensively, building a case for a new kind of political leadership, a form of sate socialism that would expand democracy and preserve community. Australian political leader Alfred Deakin, for example, traveled extensively through the US and was friends with many, including Harvard philosopher Josiah Royce. Among Deakin’s political accomplishments was an Aborigines Protection Act and a Water Supply and Irrigation Act, both of which supported White settler colonialism. This sort of state involvement and action was central to conceptions of a muscular progressive government (as well as the focus on many progressive scholars and thinkers). Deakin would later serve as Australia’s prime minister, effecting a legacy that structured Australia through the early part of the twentieth century.

Lake gives close attention to the Australian Ballot, or “secret ballot,” a reform that swept through the United States. Massachusetts was the first to adopt it in 1888 and with in a decade it was the norm in American elections. In years prior, political parties gave voters a printed ballot and voting was a public exercise. Through the Australian reform, the state printed ballots and voting was done in secret. It was very well received and scholars have shown how it reduced turnout of immigrants. The reform, in other words, was not about expanding the franchise and democracy. Lake highlights how an Australian reformer, Catherine Helen Spence, gave more than a hundred talks in her travels across the United States in 1893, advancing multiple reforms and the Australian ballot. Importantly, Spence’s push for proportional representation was not favorably received.

Many key leaders in the United States met with or became connected to Spence. Women reformers increasingly were able to take important roles in the US and Australia, especially when it came to issues around suffrage. In Australia, women won the right to vote and stand for election in 1902. Lake does not go deep into the history of the fight for women’s suffrage in the US. Rather, she explores how issues of women’s rights were framed by international exchange. One of the first women to stand for parliament, Vida Goldstein, figures prominently in this narrative – as well as her time in the United States and her visit with President Roosevelt.

Progressive New World investigates other progressive themes, including child reform, labor policies and social works. Lake calls out, in detail, the complaints voiced by indigenous peoples on both sides of the Pacific regarding state-sponsored paternalism. This proved especially true in issues of education.

Lake’s rigorous scholarship gives the narrative a close-to-the-source veracity. Surprisingly missing is a high-level summary that pulls these threads together. The pieces are all present. Moreover, the very terms employed through out beg for interrogation. What does it mean to be a settler? In an urban environment, such as Chicago, or the Australian frontier, settlement houses and white settlers seemed to employ similar language and tools. How did that identity, and the values it presented, affect future generations understanding of the role of government and political leadership?

I am profoundly impressed by the Marilyn Lakes work. Furthermore, I am especially keen on seeing how a new generation of thinkers respond to her book and deepen a new understanding of progressivism.

David Potash