Hispanics and the KKK in the 20s

Outstanding historical research is near – and the findings can be quite enlightening.

The Ku Klux Klan was formed in the years after the Civil War as a paramilitary terrorist organization, committed to assuring white rule in the defeated states of the Confederacy. The KKK spread violence, fear and death, murdering thousands, until the US federal government stepped in and through military, police and judicial action, suppressed it. The KKK returned in a new format in the 1910s, growing in size and influence. The early twentieth century Klan grew through mass marketing techniques, along with white robes and communal events – cross burning and lynching. Membership was possibly as high as 8 million by the middle of the 1920s. Numbers, though, dropped precipitously by the end of the decade. Ever since the KKK has existed as a fringe organization, focused on white nationalism.

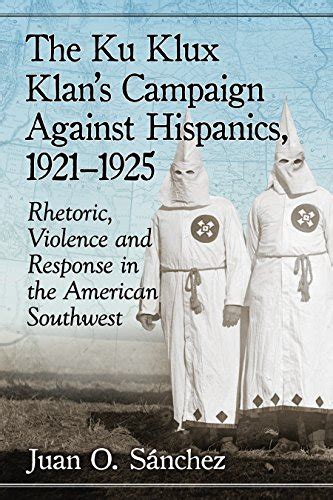

The Ku Klux Klan’s Campaign Against Hispanics, 1921-1925, a thorough work of history, was written by Juan O. Sanchez in 2018. The book is the result of several decades of rigorous research by Sanchez, who tracked down and collected numerous primary and secondary source documents from the period. He focused on Spanish language publications, but as he learned more about the period, Sanchez’s reach extended. The book is a testament to dogged investigation and systematic study. It aims to document facts, not make arguments, and it does so extremely effectively.

Between a strong introductory overview and a clear summary, Sanchez’s chapters look at Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and Colorado, and California. The Klan had a stronghold in Texas with more than 300 local organizations in the state. 1922 marked the KKK’s greatest electoral successes. The Klan was virulently anti-Mexican and it was only in the cities with large numbers of Mexican American was there organized anti-KKK resistance. The Mexican government was also an influence in protecting Hispanic Americans’ rights. Sanchez’s research highlights the many ways that the Spanish-speaking local press advanced pro-American anti-Klan arguments, as well as the rhetoric of KKK publications and editorials. The story was similar in other states, though the influence of the KKK was strongest in Texas. Sanchez shows how local conditions and opportunities framed local discussion, debate and action across the Southwest.

Big picture, The KKK’s Campaign Against Hispanics highlights the broad acceptance by many White Americans that Mexican Americans were dangerous criminals, robbing native born Americans of jobs, opportunities and wealth. The KKK repeatedly castigated Mexican Americans as a “mongrel race” with tendencies towards drunkenness, laziness, and criminality. Speaking Spanish was called un-American. Importantly, Sanchez’s sources underscore the KKK’s deep antipathy towards Catholicism. Religion and race were used complementarily by the Klan, which had deep ties to local Protestant churches and leadership. Mexican-Americans, they insisted, were not “real” Americans. God’s national order, the Klan affirmed, had Protestant white Americans at the top. Moreover, as Sanchez’s work documents, the KKK was as anti-Hispanic as it was anti-Black.

The KKK’s rise in the first half of the 1920s reflected long-standing trends in American society and politics. During this period controls over unions increased, immigration was great constricted, and a wide range of non-white groups were targeted. Happily, by the latter half of the decade more inclusive voices prevailed in the Southwest, thanks in great part to the organized resistance led by Spanish-language newspapers. Juan Sanchez’s scholarship ably documents a history of racism, intolerance, and resistance. It is history well worth studying and considering.

David Potash