War & Survival

When we think about war, we want to find heroes and villains, to craft lessons of morality. The violence and horrors of war demand that we come up with reasons and purpose. Without, it is all too terrible to contemplate. There can be no learning from random chaos. Nor is it worth our time to investigate or retell stories of empty violence. Consequently, we search for sense-making and meaning when talking about war, the reasons why and what it can teach us. Likewise, we hunt for lessons in the stories of individuals caught up in conflict. The wish is to make the conflict intelligible or understandable – even when what happens in war cannot be truly comprehended. There’s a basic human need to find some sense in the insensible.

Americans characterize World War II as a “good war.” Pledged to democracy, the US was the victim of a surprise attack by the Japanese and few villains have ever matched the evil of Nazi Germany. From the war’s onset, America claimed the moral high ground. In many ways it’s an accurate perspective. Studs Terkel cemented this interpretation in his fascinating and best-selling oral history, The Good War. It makes me wince when I hear “the good war” dropped in conversation. World War II was a global conflict and America was far from the only decisive participant. Many of the histories of the war are not about good, bad or morals. They are about awful circumstances and people trying to stay alive. There is not much good in that.

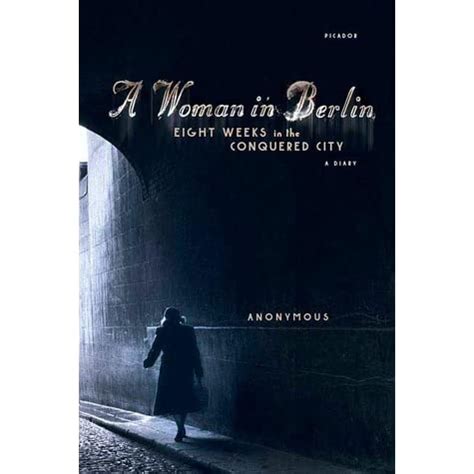

A Woman in Berlin: Eight Weeks in the Conquered City is a diary of survival. Written by a female German journalist as the Soviet army took over the city in 1945, it is a harrowing and extraordinary first-person account, pragmatic and clear-eyed in its detail. She tells us about day-to-day struggles for food, water and shelter, about death and dying, and about rape. The narrator is raped repeatedly by Soviet solders, as were thousands upon thousands of German women. Historians have not determined how many Germans were raped at the end of World War II by Allied forces, but the numbers are astronomical. Estimates range into the millions. Sexual atrocities at the end of war were pervasive, under-reported and for decades, ignored. As more scholars are realizing, sexual violence is a constant part of warfare. Rape in wartime is war by another means.

The author of A Woman in Berlin published her diary as a book anonymously in the 1950s. It was widely read in multiple languages and ignored in Germany. The author, who died in 2001, refused to have it republished in her lifetime. An updated translation into English came out in 2005, forcing a re-reckoning of the book and ready assumptions about the war’s conclusion. The arrival of peace in Europe was far from peaceful The book upends conventions of who is a victim, who is a criminal, and how and what sort of choices are possible in wartime.

At end of the war, Berlin was mostly inhabited by women, children and the aged. These people bore the brunt of the invasion, just as they had suffered through much in the past few years. We do not immediately think of German citizens as victims. They were, though, and none of the survivors in A Woman in Berlin had agency when it came to German politics or military strategy. They, like most people most of the time, simply looked to the basic needs and wants of everyday life. The immediacy of the author’s experience captures this and more, from the Soviet’s fascination with collecting wrist watches to what it felt like to stay in a bomb shelter during a raid. Our author is brutally honest, with herself and in her conversations with others. Knowing that rape is unavoidable, she seeks out an officer to protect her and to limit the possibility of random violence and rape. It was a decision driven by necessity. She wonders if she can call that a relationship in those circumstances. It was consensual to avoid rape.

A Woman in Berlin is as accurate a story of World War II as any traditional tale of heroism in battle or derring-do in resistance. The author’s prose rings true. Her voice, her language, her descriptions have tremendous integrity. I have a sense that the author’s disciplined writing, her commitment to her journalism, gave her a sense of self in a time of great pain, terrible choices and uncertainty. No one knew what the next day might hold.

The author notes the emptiness of Nazi male posturing and the collective disappointment of German women. It’s an important reminder when we place people on pedestals or talk about “good” wars. Certain conditions may make war necessary. Study it, live through it, or think about it, though, and there’s but one conclusion: do not celebrate war. William Tecumseh Sherman, a US Civil War general, summed it up. “Some of you young men think that war is all glamour and glory, but let me tell you, boys, it is all hell.”

David Potash