Atwood’s Chilling Genius

Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, published more than thirty-five years ago, remains a vibrant and troubling work of dystopian fiction that can still feel all too prescient. The Handmaid’s Tale has invaded our collective consciousness; it is a cultural force that has been adapted to television, movies, theater and even the opera. Along with Huxley’s Brave New World and Orwell’s 1984, it stands as a defining vision of a possible awful future.

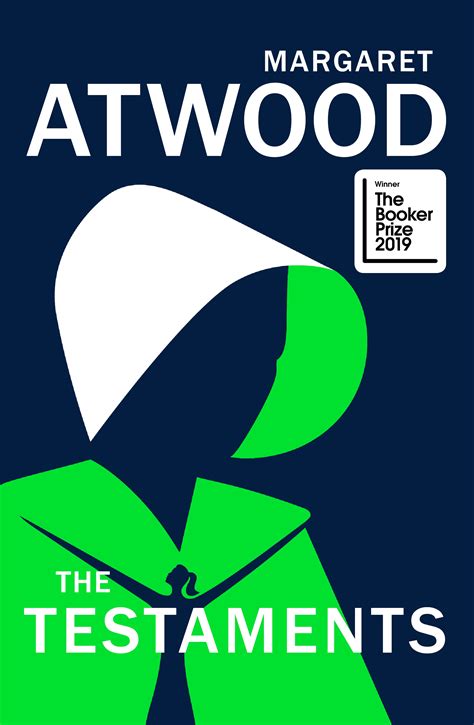

In 2019, Atwood revisited Gilead, the fictional country of Handmaid’s Tale fifteen years on, in The Testaments, an impressive work in its own right. This novel won the Booker Prize, like its predecessor, and it, too, is brilliantly structured and frightfully smart. Atwood is a literary genius and an extremely intelligent writer. Her skills of perception, of reasoning, and of capturing complexity and making it resonate the the reader are extraordinary – and she does it without being clinical. That’s one of the many ways that her stories can be so chilling.

The violence and state-sponsored misogyny of Gilead do not shock in The Testaments. We have become familiar, over the decades, with its language, protocols and organized violence and repression. The complexities of real-life sexism and misogyny are more easily recognizable today as well. One need not go deep in a newspaper to read of women dehumanized, controlled and denied agency. Nor are these stories necessarily of faraway lands. Atwood’s acknowledgement of these and other changes is reflected in The Testaments plotting. Interweaving narrators and perspectives, Atwood gives great attention to questions of survival, of morality and choice, and of power. If The Handmaid’s Tale is akin to a fictional account of the rise of a patriarchal Nazi-like country and the early faces of resistance, The Testaments is reminiscent of life in Vichy France with its traitors, resistance, and the corruption that accompanies rule by fear.

Complicated questions of moral choice shape the novel. While we may yearn for clear cut categories of good and evil, Atwood problematizes definitions and actions. What will people do to survive in a political environment that is all about control? Die willingly or execute innocent colleagues and friends? Cultures like Gilead, or Nazi Germany, deny and twist human agency into grotesque shapes. Basic concepts of justice and fairness disappear. Darkness abounds and healthy life and relationships, which want to turn towards the sunlight and goodness, instead moves in different directions. The parallels to what is happening across the globe in our pandemic are frightening.

Atwood’s characters are carefully drawn. Their voices are distinct, their journeys independent and intertwined. The Testaments is a page-turner and a work of literature, a rare combination.

What I found most fascinating about the book is that despite its horrors and bleakness, above and beyond all the horror, Atwood still writes with hope. The Testaments paints a vivid and realistic picture of a dystopia. And yet, amid all the horror and darkness, Atwood finds small spaces for optimism, for human decency and for hope. That is a message that I very much welcome.

David Potash