Truth Stranger Than Fiction

I remember Wonder Woman when it showed up on television in the 1970s. Lynda Carter was cute but the series did not really resonate with me. I found it just a bit odd, kind of old-fashioned. I had no idea just how odd – or fascinating.

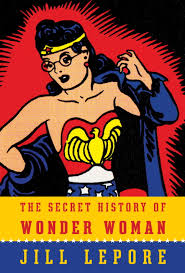

Jill Lepore, in The Secret History of Wonder Woman, explains the origins of the comic book and provides many good reasons for its strangeness. Her book has sold millions for very good reason. Sure, there’s sex, intrigue, drama, secrets and the excitement of comic books. The content is extraordinarily interesting. Lepore has done much more than report it, though. She tells a tale, raises questions, and gives us a narrative of talent and contradiction. It is really engaging popular cultural history at its best.

The story of Wonder Woman is actually the history of William Moulton Marston and his extended family. Marston was a polymath, a talented and gifted man with massive psychological issues. A mother’s boy who graduated from Harvard in 1915, paid his way through while writing screenplays, Marston also earned a law degree and a doctorate psychology. He invented the lie detector test (asking a subject questions while examining their systolic blood pressure), and bounced around Hollywood for years. He was a failure in higher education and, in many ways, harnessing his abilities for financial gain and stability. What saved him were the women he was able to bring into his life. He married to Elizabeth Holloway Marston, a hardworking, smart and highly competent woman in her own right. Olive Byrne, another smart and talented woman, was also a part of the family. Marston fathered children with both women, who maintained an elaborate fiction. Women were central to his home and professional life.

Lepore draws out the idealist circles in which Marston and his circle moved. Margaret Sanger was Olive Byrne’s aunt. John Reed was a friend at Harvard. Free love, feminism, women’s rights, psychology and science were recurring themes in the Marston milieu. All factored prominently in the creation of Wonder Woman, a product of the World War II environment. The comic strip Wonder Woman was immediately popular. Marston, sadly, contracted polio and died at the young age of 53. After the war and without his drive, Wonder Woman faded from the popular consciousness, only to be looked at anew in the 1970s with the rise of women’s liberation.

Woven throughout this complex history are idiosyncrasies, kinks, and strange coincidences – from Olive’s bracelets to Marston’s fascination with bondage. He did not acknowledge it but anyone reading Wonder Woman comics did. She and other women were constantly being chained, gagged, bound or otherwise constrained. It’s a strange narrative for a mother’s boy.

Beyond the anecdotes, what The Secret History of Wonder Woman does very well is highlight the many connections of intellectual and cultural change and production. Few successful things happen in a vacuum. Smarts always makes a difference. And sometimes it helps to be kind of odd, too.

David Potash