The Appeal of Personal Hygiene

When I was in my early 20s, I read that the advertising industry created the demand for people to shampoo. Furry animals don’t need to shampoo. Why should everyone in the twentieth century spend a fortune on shampoos and conditioners? I learned that initially my hair would feel oily, but it would then become softer, shiny and healthier. I decided to give it a try, helping my head and my wallet.

I bathed regularly and used soap – but avoided shampoos and conditioners. My hair performed as predicted. Initially gross, it became nicer as the weeks turned into months. It looked healthy but it did not smell particularly nice. I lasted about three months and have been shampooing and conditioning ever since. Every time that I do, a small voice in my head asks whether I am doing so because of personal choice, societal pressure, or manipulation by the advertising industry.

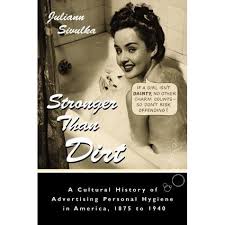

That voice grew a tad louder as I worked my way through Juliann Sivulka’s engaging book, Stronger Than Dirt: A Cultural History of Advertising Personal Hygiene in America, 1875 to 1940. Sivulka, now a professor of American Studies at a Japanese university, is a rarity among academicians. She has practical hands-on experience as a marketer and consultant as well as formal training as a scholar. Those dual perspectives help her immensely in laying out a fascinating story of how Americans became convinced that they need to buy and use soap.

Over the centuries different cultures have dealt with hygiene – personal and for their clothes – a variety of ways. Those without resources rarely washed. In classical Greece and Rome, those with funds scraped themselves, anointed themselves with oils, and had their clothes washed in urine. Soap was homemade until the 1800s and only affordable after mass manufacturing. In the United States, the push for hygiene was aided by the Union Army in the Civil War.

Sivulka’s book provides a helpful periodization to the rise of soap in the home and the social importance of cleanliness. From 1875 – 1900, the development of mass marketing and mass consumption is the main story. The first two decades of the twentieth century witnessed a proliferation of arguments made to women consumers about the importance of personal cleanliness. Women were targeted to buy and use soap for sex appeal and for health. Then, as today, women make most household purchases. Soap companies’ appeals became more sophisticated and increasingly tied to the mass communication from 1920 – 1940. It was, and remains, very big business. By the start of World War II, American society as defined by the middle class had high expectations for soap, for regular washing, and for clean clothes. Rounding out Sivulka’s narrative is a chapter highlighting the differences in the African-American market.

Stronger Than Dirt is solid cultural history. The narrative is grounded in primary sources with a focus on advertisements. Sivulka avoids theoretical claims and instead zeroes in on behavior, impact, and what the evidence looks like. She is not particularly interested in questions of morality. What excites her are effective campaigns and tangible signs of change. The growth of personal hygiene and soap took place, she argues, because of effective products and advertising, and because American consumers wanted it to happen.

Stronger Than Dirt is the kind of history book that is fun to teach. Evidence is easy to understand and discuss. It is clearly written and memorable. Most of all, students would find it relevant with clear connections to our world today. My hunch is that it would raise many questions – but that they would still use soap.

David Potash