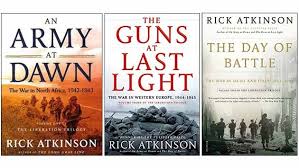

Guns At Last Light: The Good War Done Well

In 2013 Rick Atkinson finished the third and final volume of his popular history of the United States military in the WWII Atlantic theater, The Guns at Last Light: The War in Europe, 1944-1945. It is the best kind of history for the broader public: well-written, informative, and driven by a clear focus. World War II is reputed to be humanity’s largest collective enterprise. It is damned difficult task for an historian to capture the scope of the conflict and still make it understandable. Atkinson handles the challenge with skill and verve.

The first two volumes, An Army at Dawn: The War in North Africa, 1942-1943, and The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944, are equally well written. The first garnered a Pulitzer Prize. With the third in place, it is possible to see Atkinson’s strengths and weaknesses more clearly. The volumes, too, drive home the importance of revisiting the war and what it meant to America and the world. There are no easy answers when it comes to World War II.

Atkinson is an expert and mixing personal details with broader, well-established history. He knows how to maintain drama and interest with just the right quote culled from a journal or letter. To his credit, Atkinson never lets the reader forget that this was not just an international conflict pitting organization against organization. It was a battle among people. Maintaining that agenda, without losing sight of the larger shifts, makes for gripping history.

He is also writer with an expansive vocabulary and a love of rich prose. With a less sure hand, or a topic less important, the florid language might seem overdone. Considering he is writing about a war that killed 60 million, extremes are necessary.

On the other hand, Atkinson is not primarily an historian of battles or strategy. These books are not the best resource to analyze the strengths and weaknesses of the Normandy campaign or to consider supply line challenges. Atkinson mentions them, to be sure, but they are referenced in terms of people and ideas, not as examples of grand design. Further, the Atlantic Theater is best understood within the context of a global conflict. Atkinson’s theme – what the US military did and experienced – is valid. However, thoughtful readers should realize that there cannot be one definitive account of the war.

There are many volumes looking at WWII from a range of perspectives. What Atkinson has done in the Liberation Trilogy is make the heroic efforts of the United States military in the Atlantic Theater, warts and all, with its incomprehensible scale, and human sized. It is accessible intellectually and emotionally. It is an impressive achievement.

David Potash