Quiet Dignity

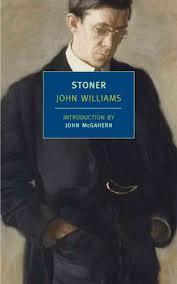

John Williams‘ Stoner is a novel well worth time and consideration. Originally published in 1965, the book was well-reviewed but far from a best-seller. After falling out of print it was reissued in 2003 and has been steadily gathering attention, praise, and sales. A gift from an English department colleague, it is a book for writers and academics. It is not a flashy book. Stoner lingers, its quiet simplicity raising very hard questions.

John Williams‘ Stoner is a novel well worth time and consideration. Originally published in 1965, the book was well-reviewed but far from a best-seller. After falling out of print it was reissued in 2003 and has been steadily gathering attention, praise, and sales. A gift from an English department colleague, it is a book for writers and academics. It is not a flashy book. Stoner lingers, its quiet simplicity raising very hard questions.

The plot is biographical. A lifelong academic, Stoner, enters the University of Missouri as a student and becomes an English professor there, teaching until his death. The product of poor, taciturn farmers, Stoner’s life is quiet and marked by frustrations, some realized, others just endured. He has an unhappy marriage, a difficult relationship with his daughter, and a brief affair that gives him a window to passion and joy. Williams treats Stoner with dignity.

Passive in many areas, life happens to Stoner. He is not a planner. What marks Stoner’s existence is his teaching and his connection to literature. It is, in many ways, a novel about the life of an academic teacher. In sketching out that existence, Williams expertly highlights the petty cruelties and the culture of constraint that accompanies life as a professor. There are few victories and more defeats. The steady toil of class after class, semester after semester, is reminiscent of the cadence of farm life and its steady, unyielding demands. Unflinchingly honest, Stoner paints a grim picture.

The beauty of the book comes from its prose. It is deliberate without being fussy, crafted like a small intricate box without screws, nails, or glue. It coheres and shines, even as the arc of Stoner’s career and life shrink.

David Potash