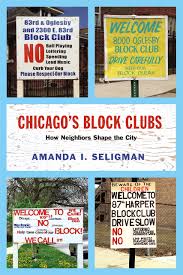

Chicago’s Block Clubs

Chicago is often described as “a city of neighborhoods” and there is much to that claim. When meeting someone from Chicago, more often than not they will immediately volunteer their neighborhood. “Oh, I’m a South Sider” or “Wrigleyville” or “Bronzeville.” It seems to be especially true for life-long residents of the city.

Historically, local Chicago communities have carried a host of associations along with their geographical boundaries. Neighborhoods were known for certain industries or employment (steel, meatpacking, transportation), with a particular race or ethnicity, or for a parish or organization. Neighbors were invested in their local community. Figuring out the nature and meaning of that local attachment is the focus of Amanda I. Seligman’s Chicago’s Block Clubs: How Neighbors Shape the City. A professor at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Seligman is interested in urban history and questions of community.

Historically, local Chicago communities have carried a host of associations along with their geographical boundaries. Neighborhoods were known for certain industries or employment (steel, meatpacking, transportation), with a particular race or ethnicity, or for a parish or organization. Neighbors were invested in their local community. Figuring out the nature and meaning of that local attachment is the focus of Amanda I. Seligman’s Chicago’s Block Clubs: How Neighbors Shape the City. A professor at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Seligman is interested in urban history and questions of community.

The book is closely researched hyper-local history about activities for which there is often little by way of written record. Seligman overcame the research challenges by working, in her words, where there was archive material – in the light. Block clubs are informal neighborhood groups. Totally voluntary, they became a fixture of Chicago in the early half of the 1900s initially through the efforts of the Chicago Urban League to help African-Americans in the great migration north. They were not just for African-Americans, though. Many other groups organized and supported block clubs. Clubs sprouted throughout the city during World War II. The numbers of block clubs have declined – bearing in mind that there is no official “count” – but they still are an important part of the Chicago landscape.

Anchoring the book are the records of the Hyde Park Kenwood Community Conference, a block club with a robust archive. Herbert Thelen, a long-time professor of education at the University of Chicago, was HPKCC’s driving force. Seligman’s book, interestingly, does not study block clubs through chronology and the shifting priorities of Chicago’s history. Instead, she organized her observations into clusters: why block clubs matter, how they were developed, and their primary functions – beautification, local improvements, sanitation and regulation. We gain a strong sense of on-the-ground dynamics and activities, but missing are the clubs’ roles in the larger context of Chicago politics, economics, and change.

David Potash